Four Ways of Measuring the Distance

Between Alchemy and Contemporary Art

James Elkins*

Abstract: Alchemy has always had its ferocious defenders,

and a small minority of artists remain interested in alchemical meanings

and substances. In this essay I will suggest two reasons why alchemy is

marginal to current visual art, and two more reasons why alchemical thinking

remains absolutely central. Briefly: alchemy is irrelevant because (1)

it is has been a minority interest from early modernism to the present,

and therefore (2) it is outside the principal conversations about modernism

and postmodernism; but alchemy is central because (3) it provides the best

language to explain the fascination of oil paint, and (4) it is one of

the best models for understanding the contemporary aversion to full logical

or rational sense.

Keywords: alchemy, aesthetics, modern art,

postmodern

art.

Introduction

This essay, which I hope hovers between art history, the history of chemistry,

art criticism, and contemporary art, was born of a series of skeptical

engagements with artists who use chemical symbols in their work.[1]

For several years I have been writing about the disconnection of science

and art.[2] In particular I have gotten interested in

the lack of living connection between alchemical images and contemporary

art.[3] There are the inevitable counterexamples, including

Roald Hoffmann’s collaboration with the artist Vivian Torrence, but the

exceptions prove the rule: chemistry and alchemy have little to do with

contemporary art.[4]

What I have in mind here is a meditation on the distance between contemporary

art practice and the history of chemistry. I do not intend to make a comprehensive

review of the literature, but to assay the major points of connection and

disconnection between the fields.

Alchemy’s Babel of symbols – its ‘seeds’, menstrua, Eves and Adams,

its greenlions – has cut it off from other disciplines, especially since

the Enlightenment. And for their part, alchemists tried to swallow neighboring

disciplines, mixing them together into a new Babel: folklore, mythology,

witchcraft, medieval mysticism, botany, anatomy, agriculture, medicine,

color theory, metallurgy, and the study of music were all incorporated,

at one time or another, into alchemical doctrines.

It stands to reason, then, that alchemy has become a field of study

for people in various modern disciplines: the history of chemistry, the

history of mysticism and religious thinking, the history of natural philosophy,

the histories of mining and technology. Scholars in those fields mine alchemy,

just as it mined them, and try to classify and elucidate alchemy’s many

misunderstandings and borrowings.

In terms of fine art, alchemy has long been a place Western artists

could go to veil their work in obscurity. From Ferrara in the fifteenth

century to the Venice biennale, artists have drawn on alchemy, and art

historians have worked hard to elucidate the artists’ intentionally hidden

meanings. So art history and even art criticism should be added to the

list of disciplines that are legitimately concerned with alchemy.

Yet always there is the question of the relation between alchemy and

the disciplines that are interested in it. In the seventeenth century the

principal questions were the relation of alchemy and the church, and the

emergence of scientific practices. The relation of alchemy and the humanities

(that is, the university) was a difficult question then, and even now it

is the object of debate. I do not know any university that would admit

a professor of alchemy. Such a person might teach Jungian theories in the

Psychology Department, or meditative theories in the Religious Studies

Department, or even the philosophy of substances in the Philosophy Department.

The ‘alchemists’ who work in universities are all, to my knowledge, either

historians of chemistry or historians of medicine or art – in other words,

they are ‘alchemists’ only in the sense that they study other peoples’

beliefs about their subject, not the subject itself. In that respect alchemy

remains outside the university, as it always was in European universities

from the Middle Ages onward.

When art historians study alchemical images, the historians themselves

become part of this unresolved history. An interest in alchemical images

is a sub-specialty within, for example, the specialty of Baroque art –

and it is a problematic specialty at that. The historians who make alchemy

their particular interest are sometimes looked on as eccentrics: their

methodology may be impeccable (I mean, good archival research, sound iconographic

analyses), but their choice of subject matter makes them suspect. In that

respect art historians who are interested in alchemy become one further

example of the oil-and-water problem of mixing alchemy with any ‘legitimate’

discipline.

The same observation can be made about art critics who are drawn to

the work of artists who employ alchemical symbols. They too tend to be

marginalized in the world of art criticism. People might take such critics

to be New Age spiritualists, or else to have some private spiritual agenda

that attracts them to like-minded artists.[5]

There are many contemporary artists who openly use alchemical symbols:

Brett Whiteley,[6] Krzysztof Gliszczynski, Rosslynd Piggott,[7]

Sharon Walker, Leigh Hyams, Milan Mrkusich,[8] Therese

Oulton,[9] Domenico Bianchi,[10] Helmut

Dirnaichner,[11] Tommaso Cascella,[12]

Pat Martin Bates,[13] Jean Aujame,[14]

Ljuba (Popovic Alekse Ljubomir),[15] Arturo Duclos,[16]

Ian Howard,[17] Richard Mueller,[18]

Anna Hollings,[19] Claudia Schink,[20]

Dick Ket, Raoul Hynckes, and Pyke Koch.[21] All of them

are minor in the sense that they appeal to a narrow specialty public.[22]

(For an opposing view, see Sidney Perkowitz’s work; he does not concern

himself with quality, but only with the presence of scientific themes in

art.[23]) I have gotten several dozen portfolios from

such artists, who were responding to my book: none of my colleagues had

heard of any of them.

I know this phenomenon of exclusion and suspicion firsthand. When I

was researching my book on alchemy and painting, What Painting Is,

I found only a few art historians or historians of chemistry willing to

talk about the subject. I contacted real alchemists, people who teach alchemy

outside the university system, but when I proposed symposia that would

include those people along with chemists and historians of chemistry, I

was turned down. (I proposed one such conference at Cambridge University,

to a group of scholars who were advertising their interest in unusual,

non-academic subjects: but this subject was too unusual even for them.)

Some painters, historians, and critics also kept their distance from my

project. After the book was published, I started getting letters from painters

who liked the book’s approach, and I still get six or seven invitations

each year to speak at studio art departments. The book has made a certain

number of ‘converts’ among painters – people who are very enthusiastic,

and tell me that my book is the first one they have found that gives voice

to their sense of what painting is really all about. Yet the book has also

lost

me some friends, especially art historians who have read it and politely

declined to comment; and it also attracts letters from contemporary artists

who use explicit alchemical symbols in their work, or who follow Jung –

even though my book argues, explicitly, against those ways of employing

alchemy.

So what I want to do here is step back and assess the relation between

alchemy and two of the many fields it intersects: contemporary art, and

contemporary art criticism or art history. My object is to try to describe

the problematic relation between alchemy and those two disciplines (art

production and scholarship). I think the troubled relation among those

disciplines is typical of the troubled relation alchemy has long had with

science, with the humanities, with religion, and with the university.

I find there are four basic ways that alchemy can be related to contemporary

art and scholarship. Alchemy can be considered to be basically irrelevant

to contemporary art and art scholarship because (and this is my first point)

it is has been a minority interest from early modernism to the present,

and also because (this is the second point) it is outside the principal

conversations about modernism and postmodernism. On the other hand, alchemy

can be said to be central to contemporary art and scholarship on art because

(point three) it provides the best language to explain the fascination

artists can feel for oil paint, and (the last point, number four) alchemy

is one of the best models for understanding the contemporary aversion to

full logical or rational sense. I will consider the four points in order.

1. Alchemy is irrelevant because it has been a minority interest from early

modernism to the present

The histories of alchemy and art have a number of points of contact. There

have been persuasive arguments about the importance of alchemy to Joseph

Beuys,[24] Francesco Clemente, Marcel Duchamp,[25]

Adolph Gottlieb,[26] Brice Marden,[27]

Sigmar Polke,[28] John Graham,[29]

Yves Klein,[30] André Masson,[31]

Salvador Dalí,[32] Anselm Kiefer,[33]

Pollock,[34] Max Ernst,[35] Remedios

Varo,[36] Francis Picabia,[37] Jim

Dine,[38] Joan Miró,[39] and

many others. (Among pre-modern artists: Parmigianino,[40]

Dürer,[41] Teniers, Bosch,[42]

Giorgione,[43] and Breughel.) Alchemy has also been

featured in exhibitions, most prominently the 1986 Venice biennale, where

it was associated with the current revival and transformation of the Wunderkammer.[44]

I would argue that such connections are generally superficial and tenuous.

The principal reason is that alchemy is a radically incomplete source

of explanation even for the works of the artists I have named. Joseph Beuys’

Tallow

(1977), for example, is a massive cast of the unused space at one end of

a pedestrian underpass. It conforms to several important alchemical concepts:

it involves transformation, and uses its material in an essentialist manner.

Yet an account of Tallow in terms of alchemy would be inadequate

because so many other themes are more important. (For instance, Tallow

connects to Beuys’ critiques of urban space, of architecture, of use-value

and exchange-value in modern life.) Gottlieb’s

Alchemist (1945)

and Pollock’s Alchemy (1947) are one-off pieces, typical of an interest

in alchemy that swept the New York art scene in the mid 1940s. In neither

painting are the alchemical symbols the most important elements in the

paintings. In Gottlieb’s case, the alchemical pictographs were interchangeable

with non-alchemical ones. In Pollock’s painting the symbols are so subtle,

and so integrated into the painting, that there is no reason to suppose

Pollock even intended them as such. Even Kiefer’s enormous Nigredo,

explicitly named after a stage in the alchemical process, cannot be adequately

glossed as an alchemical image: it is ultimately about history, memory,

and national guilt. As Ann Temkin has pointed out, the black is preeminently

the morally darkened soil of Germany.[45]

Let me suggest four conclusions: first, few modern artists out of the

total number were influenced by alchemy; second, the influence was often

not alchemy proper but the idea of it; third, not much of any given

artist’s production can be explained by appealing to alchemy (with the

exception of minor artists such as the ones I listed earlier); and fourth,

what is explained is often not the work’s most important features.

2. Alchemy is irrelevant because it is outside the principal conversations

about modernism and postmodernism

By ‘principal conversations’ I mean questions of the place of cubism and

surrealism, the importance of abstract expressionism, the value accorded

to abstraction, the end of naturalism in Cézanne and postimpressionism,

the rise of dada and conceptual art, the question of painting after minimalism

and support/surface, the various competing definitions of postmodernism.

Here the exceptions are especially interesting. I would name Forrest

Bess, the mid-century psychotic visionary artist from Texas who caught

the interest of the historian Meyer Schapiro, and Marco Breuer, a contemporary

photographer.[46] Bess and Breuer are very different

artists, but their work is significant. As Schapiro pointed out, Bess’

paintings are among the very few authentically visionary artworks, uninfluenced

by notions of ‘outsider art’. Bess is especially important given the current

interest in naïve art and outsider art. Breuer does not speak of his

art in alchemical terms, although it could easy be argued that transformation

is its central trope. He is, I think, one of the most interesting photographers

who are currently working. He makes photographs without light, by scratching

and burning photographic paper in the dark. The heat and friction produce

chemical reactions that are then developed, producing ‘minimalist’ forms,

grids, lines, and scratches.

But there are precious few artists whose work is alchemical and also

part of the mainstream of conversations on modernism and postmodernism.

The major problems and issues of modernism and postmodernism have nothing

to do with alchemy. To make connections between contemporary art and alchemy

it is necessary to back up, and speak less in terms of symbolic content

and more in terms of abstract similarities.

3. Alchemy is central because it provides the best language to explain

the fascination of oil paint

This is the contention of my book, What Painting Is. There I argue

that alchemy is the best language for talking about substances: thickness

and weight and heft (they are all different), viscosity and stickiness

and tackiness and goo (again all different), color and tint and hue and

chroma and the ‘feel’ of color.

That is the basic reason I wrote the book. It is not Jungian, and it

does not have much to do with alchemical symbols. I was interested in relating

some of the universal problems of oil painting in the West – the managing

of light and dark, the systems of colors – to the words alchemists

invented to describe the phenomena they saw in their vessels and crucibles.

I thought that painters often love the textures and even the smells of

oil paint, but have no words to convince non-painters, including historians.

The idea was to adopt the words alchemists had invented to give voice to

the painters’ love of the paint itself. This is how I put it in the book

(p. 5):

To a nonpainter, oil paint is uninteresting and faintly unpleasant.

To a painter, it is the life’s blood: a substance so utterly entrancing,

infuriating, and ravishingly beautiful that it makes it worthwhile to go

back into the studio every morning, year after year, for an entire lifetime.

As the decades go by, a painter’s life becomes a life lived with oil paint,

a story told in the thicknesses of oil. Any history of painting that does

not take that obsession seriously is incomplete.

Many of my colleagues in art history go on the assumption that painters

want to be out of the studio as quickly as possible, because they think

of the studio a bit like writers think of their computer keyboards. But

in my experience serious oil painters love oil: they just lack the

words to describe their attachment.

For those reasons the book What Painting Is stays away from artists

who are literal about alchemy, and use alchemical symbols and so on – all

my examples in the book are mainstream artists, from Sassetta and Tintoretto

to Rembrandt, Dubuffet, Bacon, and Pollock.

I used alchemy only because I had no alternative. Like painters, spent

their lives peering into their vessels, looking for colors, for changes

of nature, for the mixtures of the elements, for fixity and liquidity and

the propensity to stain or evaporate or sublimate: and that is exactly

what painters do.

Hypostasis and transcendence are absolutely central to what painters

think about, even though most would not put it in those terms. Some painters

would talk about their paint in terms of transcendence, illusion, or the

ability to signify beyond the paint’s raw ‘materiality’; and for all of

those things, I think alchemy’s spiritual allegories of transubstantiation

and hypostasis are ideal. One art critic called my book ‘moony’, and it

is moony (i.e., ridiculous, lunatic) if it is taken literally, as

an attempt to claim that all painting is secretly about alchemical

allegories: but it is not so moony to try to find an adequate conceptual

frame for something that painters are still very engaged with, even if

they don’t have a good vocabulary for describing it. There is a debate

in contemporary art history and criticism about ‘base materialism’, the

impossibility of transcendence, and the purposes of painting after minimalism:

but that discussion leaves the majority of working painters out

in the cold: they still believe painting’s purpose is some kind of ‘transcendence’

– some way of getting beyond the literal reference to the support and medium

themselves – but they have been left out of the current critical discussion.[47]

I still think that book is on the right track: it is a way to revive,

or change, alchemy so that it can continue the work it did for past generations.

4. Alchemy is central because it is one of the best models for understanding

the contemporary aversion to full logical or rational sense

This is the broadest and most general connection, I think, between alchemy

and contemporary art. The strongest continuity between alchemy and 20th-century

art is best sought not by tracing direct iconographic evidence of alchemical

thinking, nor even by finding a vocabulary for paint itself, as I did,

but by looking in particular at strategies for increasing mystery

by introducing fragments of language or allusions to language

into predominantly or originally ‘purely’ pictorial settings.

I want to suggest a general term, the feeling of meaning, which

I think captures this affinity. The idea on the part of artists is, generally

speaking, to increase the quotient of irrationality until the picture only

seems

to have meaning, or feels like it has meaning. First, however, I

want to make several specific observations about the relevance of alchemy

in this hermeneutic.

From the fourteenth to the early eighteenth centuries, alchemical illustrations

achieved a richer vocabulary, a greater expressive freedom, and a more

articulate economy of ‘verbal’ and ‘visual’ elements than other kinds of

pictures before the twentieth century.[48] Contemporary

painters who work with improvised, private symbols can do no better than

study the alchemical illustrations, with their dense mingling of the visual

with the linguistic in all its forms: from simple typographic lexeme to

calligraphic and multiple symbol, from hieroglyph to elaborate emblem,

from device to perspectival, theriomorphic, and animate heraldry.

In this respect it is important to recall that alchemical illustrations

are in large measure feral outgrowths of domestic Renaissance emblems,

which are in turn partly misunderstandings of Egyptian hieroglyphics. Because

Renaissance artists had no clear sense that one might want to write

in

hieroglyphics, artists such as Albrecht Dürer, following the humanist

Willibald Pirckheimer, felt free to expand and elaborate the hieroglyphic

symbols into little pictures (which Renaissance artists continued to call

‘hieroglyphics’). A well-known example is Horapollo’s simple, codified

‘dog’ – once a hieroglyphic sign, which Dürer made into a textured

drawing with expression and contraposto. It became a little picture;

it would take five minutes or more to draw, making it entirely impractical

as a graphic element in a written script.[49]

In that way writing, emblems, and pictures were tangled from the outset.

Yet in contrast with contemporary painting, Renaissance emblems are entirely

intelligible once one reads the accompanying motto (the inscriptio)

and verse (subscriptio). In Guillaume de La Perrière’s La

Morosophie, for example, an owl disturbs two sleepers.[50]

The author explains the meaning: just as an owl’s hooting will frighten

sleepers, so will good people be shocked by a slanderous man’s words. The

‘visual component’ – the pictura – is crudely done, and attracts

no special attention.

Alchemical emblems tended to increase the pictorial content, and delimit

or obscure the inscriptio and subscriptio, turning them into

ciphers. Those strategies meant that viewers were sent back to the images

in their quest to understand the emblems. The result, in technical terms,

is pseudolinguistic: the emblem appears to comprise a sentence,

as it does in the traditional non-esoteric emblemata, but it cannot be

read. Postmodern figurative painting by artists as different as Eric Fischl,

Francesco Clemente, Susan Rothenberg, and Ross Bleckner, becomes pseudolinguistic

whenever a private story is presented as a picture. Viewer and maker share

the knowledge of the presence of private meanings, but unless the artist

explains the work, the viewer does not share the private meaning and the

work remains enigmatic: it is indecipherable, pseudolinguistic. The ultimate

source of such pictures is the Renaissance misunderstanding of hieroglyphs,

and the Baroque elaboration of that misunderstanding in the form of alchemical

and esoteric emblems.

Here is an example from alchemy (figure 1). Over a Lowlands canal four

fiery spheres appear, representing the four Fires of the Work.[51]

This time the text, Maier’s Atalanta fugiens, offers four interpretations:

the four fires are Vulcan, Mercury, the Moon, and Apollo; or true fire

(ignis verò), natural fire (ignis naturis), unnatural

fire (ignis innaturalis), and antinatural fire (ignis contra

naturam); or fire, air, water, and earth; or the dragon, the menstruum,

water,

and Sulphur & Mercury.[52] The fires build skyward,

just as the alchemist aspires to the height of the phoenix’s pyre and its

eternal regeneration. In this way the commentary compounds the four spheres

with a fourfold interpretation, instead of explaining the single mystery

by a single meaning – a typical gesture.

Figure 1: Emblem XVII from Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens

(Oppenheim: Hieronymus Gallerus, J. Theodorus de Bry, 1618).

Here the landscape is a larger player. It is only partly drawn into the

meanings of these apparitions: the outhouse may allude to the earthly origins

of the alchemical process (which was often connected to the four humors,

and began with black, the bilious humor, and the materia prima),

and the canal water suggests the menstruum and, as Maier says, it

indicates that alchemical fires are "waters that do not wet the hands",

as quicksilver does not. Yet these are only details in the landscape. There

is still the basic question, not meant to be asked but impossible to squelch:

Where is this? What landscape, what country? The only available answers

– that it is a dream, a fable, or a vision – are all cut off by the picture’s

commentary, which proclaims symbolic meanings. The mystery of four flaming

spheres on a canal is not resolved by a list of allegorical meanings, and

we are thrown back on the apparition. We begin again, looking into the

flames, watching the reflections, wondering if those people on the boats

see the spheres at all. An earthly flame or storm engulfs the right half

of the sky. Is it, too, a symbol? Or a conventional device added by the

engraver? Is the entirety of the plate a vision? (The darkened foreground

makes it seems as if the spheres glow, but they sit in a pool of shadows.)

What forms are ‘natural’, and what is to be included in the enuntiagraph,

the symbolic sentence that must, in the end, pronounce the meaning of the

picture?

The same, I want to suggest, happens in contemporary art, although the

language of alchemical emblems has yet to be applied to it. I choose an

example from photography, partly to show that these phenomena are nearly

ubiquitous. (The avoidance of meaning, and the inheritance of ideographic

images and emblemata, may be as close as it is possible to come to a grounding

definition of the current state of image making.) The example is Susan

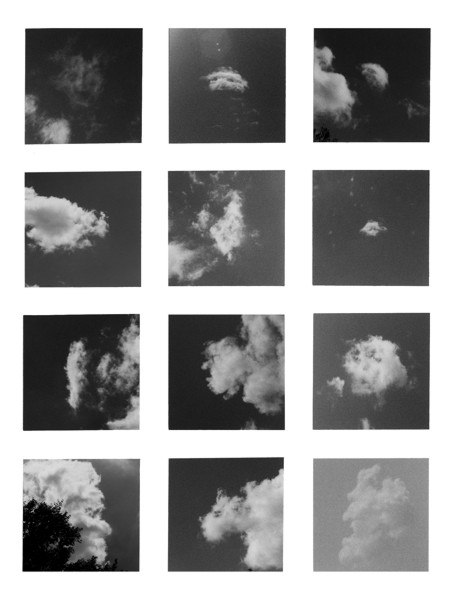

Eder’s collection of photographs called Cloud Faces (Figure 2).

Eder is a versatile photographer whose work can be traced most clearly

to the institution of the Wunderkammer (roughly: the world as a

source of wonder, rather than a repository of science), which is currently

undergoing an intermittent renascence in visual art. But the deeper current

here, the one that underwrites even the inconsistent revivals of the Wunderkammer,

is the tradition of emblems without texts. Here there is no inscriptio

or subscriptio, as in La Perrière, and not even any accompanying

mystifying text, as in Maier (although gallerists supply such texts with

exhibition catalogues). The clouds are simply clouds, or simply faces:

there is no clear meaning, no moral, no purpose. There is a bit of whimsy,

in this case, and a touch of wonder and playfulness: but to what end? If

it had a clear purpose, a La Perrière-style moral, it would probably

not be counted as art. I could have chosen pictures with more formal

affinity to the seventeenth-century emblems – Clemente’s and Schnabel’s

paintings often mix odd symbols with figures – but that would be a little

misleading. It’s not the formal similarities that provide the deepest affinities,

but the suspension of clear meaning.

Figure 2: Susan Eder, Cloud Faces, 1984, detail. Photos

on 16 x 20" mountboard. Courtesy of the artist.

A strategy of current painting, as well as of the old alchemists, is to

increase the feeling of meaning, the sense that meaning is present

without the forced quality of naked written meaning. A feeling of meaning

is an intuition of meaning, the result of mingling ‘word’ and ‘image’,

emblem and picture. The result is an incomplete fusion: in viewer’s terms,

it

asks for incomplete reading and incomplete viewing. Recent painting

has achieved objects that are neither word nor image, and they stand directly

on the heritage of alchemy. That, I think is the deepest connection between

the history of alchemy and contemporary art, and one that is still waiting

to be explored.

Notes and References

[1] This essay was originally presented at a conference

on alchemy at the University of Århus, Denmark, 2001. I thank the

participants and an anonymous reader for suggestions.

[2] See my reviews of Martin Kemp, The Science

of Art (Yale, 1990), Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 54,

no. 4 (1991), 597-601; of Picturing Science, Producing Art, ed.

by Caroline Jones and Peter Galison, in Isis, 97 no. 9 (2000),

318-19; and of Eileen Reeves, Painting the Heavens: Art and Sciences

in the Age of Galileo (Princeton, 1997), in Zeitschrift für

Kunstgeschichte, 62 (1999), 580-85. A book, Six Stories from

the End of Representation: 1975-2002 (Stanford CA: Stanford University

Press, forthcoming), formally sets out the ideas in those reviews.

[3] The book What Painting Is (Routledge,

New York, 1998) contains the basic argument; see further the essay ‘On

the Unimportance of Alchemy in Western Painting’, Konsthistorisk tidskrift,

61

(1992), 21–26, which was followed by an exchange with Didier Kahn titled

‘What is Alchemical History?’, Konsthistorisk tidskrift,

64,

no. 1 (1995), 51–53.

[4] Roald Hoffmann & Vivian Torrence, Chemistry

Imagined: Reflections on Science, with a forward by Carl Sagan, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington DC, 1993.

[5] An interesting recent example is the book

Beautiful

Necessity, on women’s altars. A few examples in the book have alchemical,

Rosicrucian, and Masonic symbols; the book as a whole would be regarded

more as sociology than art history. Kay Turner, Beautiful Necessity:

The Art and Meaning of Women’s Altars, Thames and Hudson, London, 1999.

[6] Ola Åstrand, ‘Brett Whiteley’s Alkemi’,

Paletten,

58, no. 2 (1997), 40-43.

[7] Harriet Edquist, ‘The Transformations of

Rosslynd Piggott’, Art and Australia, 32, no. 3 (1995), 380-89.

[8] Alan Wright, ‘The Alchemy of the Painted

Surface: The Early Work of Milan Mrkusich, 1960-65’, Art New Zealand,

82

(1997), 44-8, 79-80.

[9] David Cohen, ‘Therese Oulton’s Painting:

The Jewels of Art History’, Modern Painters, 1, no. 1 (1988),

43-47.

[10] Elio Cappuccio, ‘Domenico Bianchi’, Tema

Celeste, 32-33 (1991) 92 [vv].

[11] Thomas Kliemann, ‘Helmut Dirnaichner: »Man

Muss Schon sehr Suchen«’, Batería, 15 (1994),

114-23.

[12] Alessandro Riva, ‘Il Vietcong dell’arte

si mette a nudo: tra simboli magici e forme dell’inconscio’, Arte,

297

(May 1998), 71.

[13] A. De Chantal, ‘Pat Martin Bates: le rouge,

le blanc, et le noir’, Vie des Arts, 78 (1975), 38-39.

[14] Jean Rudel, ‘Le retour au ‘mythe’ dans

l’oeuvre de Jean Aujame’, Archives de l’Art Français, 25

(1978), 513-24.

[15] G. R. Hocke, ‘Der Jugoslawische Maler Ljube:

Zur Charakterisierung seiner gemalten Träume’, Kunst und das Schöne

Heim, 93 no. 6 (1981), 397-404, 437-38.

[16] Gerard-Georges Lemaire, ‘Conversation avec

Arturo Duclos’, Verso, 14 (April 1999), 16-17.

[17] Ian Howard, ‘Artist’s Eye’, Art Review,

51

(March 1999), 48-49.

[18] Christine Ross-Hopper, ‘In Conversation:

Richard Mueller’, NS [Canada], 2, no. 1 (March 1992), 20-29.

[19] Emily Simpson, ‘Mute Poetry: The Art of

Anna Hollings’, Art New Zealand, 90 (Autumn 1999), 58-59.

[20] Suzanne Wedewer, ‘Begriff und Bild: Claudia

Schink’, Neue Bildende Kunst, 6 (1999), 46-48.

[21] For the last three see Jerome Coignard,

‘Une vie inquietante’, Connaissance des Arts, 571 (April

2000), 100-103.

[22] This list is culled from a work in progress,

Failure

in Twentieth-Century Painting. For further information see R.A. Coates,

The Influence of Magic on the Iconography of European Painting,

PhD diss., unpublished, New York University, 1972.

[23] Sidney Perkowitz, Empire of Light: A

History of Discovery in Science and Art, Joseph Henry Press, Washington

DC, 1996).

[24] John Moffitt, Occultism in Avant-garde

Art: The Case of Joseph Beuys, UMI Press, Ann Arbor MI, 1988.

[25] For alchemy in Duchamp see first Linda

Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the

Large

Glass and Related Works, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ,

1998; and then (all of them less reliable sources) Joan Veronice Messenger,

Marcel

Duchamp: Alchemical Symbolism in and Relationships Between the Large Glass

and the Étant Donnés, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor

MI, 1984; Arturo Schwartz, Arte e alchimia, exh. cat. of the XLII

Esposizione internazionale d’arte la Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 1986;

and Pontus Hulten, Jean Clair, et al., Marcel Duchamp, abécédaire,

approches critiques, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre national

d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1977; John Golding,

Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,

Viking, New York, 1973, p. 90, strikes an appropriately skeptical note

in relation to the Bride.

[26] Mary Davis MacNaughton, The Painting

of Adolf Gottlieb, 1923-1974, PhD diss., Columbia University, 1981

(UMI Press, Ann Arbor, 1988), p. 137.

[27] Brice Marden: Marbles, Paintings, and

Drawings, exh. cat., Pace Gallery, New York, 29 Oct.-27 Nov. 1982.

[28] Tom Holert, ‘Arsen und Spitzenhäubchen:

Vorschläge zu Sigmar Polke’, Texte zur Kunst, 7 , no.

27 (1997), 78-87; Kathleen Howe, ‘Alchemical Researches: The Photoworks

of Sigmar Polke’, On Paper, 1, no. 2 (1996), 13-15.

[29] See Hayden Herrera, ‘John Graham: Modernist

Turns Magus’, Art Magazine, 51, no. 2 (1976), 7-12.

[30] Claudia Giannetti, ‘Retrospectiva de Yves

Klein: el salto en el vacío’, Lapiz, 13, no. 108 (1995),

52-7.

[31] Patrice Trigano, in André Masson,

ed. by Arnau Puig, Fundació Caixa de Pensions, Barcelona, 1985.

[32] M. Heyd, ‘Dalí’s Metamorphosis

of Narcissus Reconsidered’, Artibus et Historiae, 10

(1984), 121-31.

[33] Bea Dotti, ‘Anselm Kiefer: agli Inferni,

andata e ritorno’, Arte, 308 (1999), 66-67.

[34] J. Welsh, ‘Jackson Pollock’s »The

White Angel« and the Origin of Alchemy’, in The Spiritual Image

in Modern Art, ed. by Kathleen Regier, Wheaton, Illinois, 1987, p.

193; J. Wolfe, ‘Jungian Aspects of Jackson Pollock’s Imagery’, Artforum,11

(November 1972), 65-73.

[35] M. E. Warlick, Max Ernst and Alchemy:

A Magician In Searth of Myth, University of Texas Press, Austin TX,

2001; David Hopkins, ‘Max Ernst’s La toilette de la mariée’,

Burlington

Magazine, 133, no. 1057 (April 1991), 237-44.

[36] Sue Taylor, ‘Into the Mystic’, Art in

America, 89, no. 4 (April 2001), 126-29; Janet Kaplan, Remedios

Varo: Unexpected Journeys, Abbeville Press, New York, 2000; Deborah

Haynes, ‘The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious

Meaning’, Woman’s Art Journal, 16, no. 1 (1995), 26-32.

[37] Arturo Schwarz, ‘Picabia…sobre alguno arquetipos

alquímicos’, Kalías, 7, no. 14, (1995), 20-31,

177.

[38] Demetrio Paparoni, ‘The Memory of Death:

Jim Dine’, Tema Celeste, 6, no. 3 (1988), 28-33.

[39] Hubertus Gassner, Joan Miró:

Der magische Gärtner, DuMont, Köln, 1994.

[40] See Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Il Parmigianino,

un saggio sull’ermetismo nel Cinquecento, M. Bulzoni, Rome, 1970),

p. 45. Comparative material is available in the fundamental study by Sydney

Freedberg, Parmigianino, His Works in Painting, Harvard University

Press, Cambridge MA, 1950.

[41] For a recent account see Maurizio Calvesi,

‘A Noir (Melencolia I)’, Storia dell’Arte, 1-2 (1969),

37-96.

[42] See Laurinda Dixon, Alchemical Imagery

in Bosch’s Garden of Delights, UMI Research Press, Ann Arbor MI, 1981;

Madeleine Bergman, Hieronymus Bosch and Alchemy, (Acta Universitatis

Stockholmiensis, Stockholm Studies in History of Art, vol. 31), Almqvist

and Wiksell International, Stockholm, 1979.

[43] See G. F. Hartlaub, Giorgiones Geheimnis:

Ein kunstgeschichtlicher Beitrag zur Mystik der Renaissance, München,

1925. Hartlaub is critiqued in Salvatore Settis, La "Tempesta" Interpretata

(1978), translated by E. Bianchini as Giorgione’s Tempest, Interpreting

the Hidden Subject, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990, p.

52.

[44] Mino Gabriele, Alchimia: la tradizione

in occidente secondo le fonti manoscritte e a stampa, exh. cat,XLII

Esposizione internazionale d’arte la Biennale di Venezia, Electa, Venice,

1986.

[45] Temkin, ‘Nigredo (1984) by Anselm

Kiefer’, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, 86, no. 365-366

(1990), 24-26.

[46] Bess is discussed in my Pictures of

the Body: Pain and Metamorphosis, Stanford University Press, Stanford,

1999, and in Forrest Bess, exh. cat., ed. by John Yau, Hirschl and

Adler Modern, New York, 1988. Breuer is discussed in my ‘Renouncing Representation’

essay in Marco Breuer: Tremors, Ephemera, exh. cat., Roth Horowitz,

New York, 2000.

[47] I am thinking of Rosalind Krauss and Yve-Alain

Bois’s book Formless: A User’s Guide, Zone, New York, 1997.

[48] The problem of finding satisfactory synonyms

for ‘word’ and ‘image’ is discussed in Norman Bryson’s Word and Image,

French Painting in the Ancien Régime, Harvard University Press,

Cambridge MA, 1981. Bryson considers various alternates: the Latinate "discursive"

and "figural," "[t]he interactions of that part of our mind which thinks

with words, with our visual or ocular experience," and the near-synonyms

"optical truth," "Being," "Life," "‘being-as-image’" and "visual experience

independent of language" as against "those features which show the influence

on the image of language" (pp. 5-7). Here I have opted for ‘visual’ and

‘linguistic’, with the understanding that they are a lesser evil than the

overly restrictive and explicit ‘word’ and the optically-tinged ‘image’.

The question is pursued in, Mieke Bal, Reading "Rembrandt": Beyond the

Word-Image Opposition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991;

and my own Domain of Images, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY,

1999.

[49] See the discussion of the emblem of Maximilian

I in Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer, Princeton University Press,

Princeton NJ, 1948.

[50] Guillaume de La Perrière, La

morosophie de Guillaume de la Perriere, Tolosain, contenant cent emblemes

moraux, illutrez de cent tetrastiques latins, reduitz en autant de quatrains

françoys, Par Macé Bonhomme et a Tolose par Iean Mouhier,

Lyon, 1553.

[51] Maier, Atalanta fugiens, emblem

XVII. See H.M.E. de Jong, Michael Maier’s Atalanta fugiens: Sources

of An Alchemical Book of Emblems, Brill, Leiden, 1969.

[52] Johannes Fabricius, Alchemy: The Medieval

Alchemists and Their Royal Art, Diamond Books, London, 1994, p. 207,

for the four fires as "1) earthly fire 2) lunar fire 3) heavenly, solar

fire 4) solar, nuclear fire." This reading is pursued in context of "word-image"

relations in my Domain of Images, p. 201.

James Elkins:

Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism, School of the Art

Institute, 112 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago IL 60603, U.S.A.; jelkins@artic.edu

Copyright Ó

2003 by HYLE and James Elkins

|